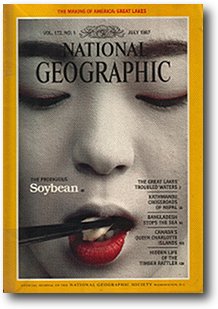

Vol. 172, No. 1; July 1987

|

| The day the foreigner came began as had many others in the lives of the Sun brothers, or, for that matter, in those of their father and grandfather. At three that morning they had let themselves into their one-room doufu shop, one of ten that prepared bean curd, the "vegetable meat" made from soybeans, for the villagers of Chao Lang near Shanghai. In the middle of the floor bulked large, dark ceramic jars full of straw-colored beans that had been left soaking overnight. The two brothers ladled the beans into a mechanical crusher, strained the mash, poured the filtrate into an iron pan set in the top of a coal stove, brought it to a boil, ladled it into another jar, and added a coagulant salt. |

On this particular morning, around ten, the Suns heard a burst of crowd noise, a hubbub of comment and exclamation, moving in their direction. |

I had traveled to China in part because the whole story began here, at least 3000 years ago, when farmers in the eastern half of northern China started planting the black or brown seeds of a wild recumbent vine. Why they did this is unclear; plants that lie on the ground are hard to cultivate, and the seeds of the wild soybean are tiny, hard, and unless properly prepared, indigestible. Whatever the reasons, the farmers persevered, and evidence suggests that by 1100B.C. the soybean had been taught to grow straight up and bear larger, more useful seeds. These changes were sufficient to add the bean to the list of domesticated plants. |  |

The enthusiasm farmers had for their new crop is suggested by some of the names given different varieties: Great Treasure, Brings Happiness, Yellow Jewel, Heaven's Bird. |

| As we talked, walking through the corridors of plane trees that line the streets of Shanghai, we would pass through the outdoor markets where, under the new economic policies of China, individuals were allowed to sell products of their own manufacture. Sometimes we would see a doufu seller, back on the streets after all these years, and stop to chat. "How's business?" I would ask. "Terrible," I would hear. "I have to stand here all day. Who can compete with state stores?" (The state stores sold a cheaper, but less tasty, version.) But Tong, after some calculations, advised me that the sellers were doing very well indeed. |

Buddhist monks are strict vegetarians, and doufu had become an important food in Chinese monastaries. For several centuries Buddhism was an upper-class religion in Japan; these social associations pushed the development of tofu and its associated soy foods in a different direction than in China. |

Perhaps the most dramatic illustration I found of Watabe's point was encountered in the Yachiyo Honten restaurant near Nagoya. Yachiyo Honten lies in Okazaki Park, on the grounds of the castle in which Tokugawa Ieyasu, the famous shogun who unified Japan, was born. The restaurant itself sits on a corner defined by a bend in the moat that once girdled the castle. Someone entering one of the small dining rooms and rolling back the wide wall screens will find himself floating eye to eye with the crowns of the maples, oaks, and alders that now grows out of the moat. And if he visit on a brilliant afternoon in October, as I did, the light flooding into the room will seem to buoy it up like a balloon and send it soaring through the color burst of autumn foliage. |  |

The chef, Teiichi Nakagawa, is a young man with a broad experience of the world; he has eaten at, and was unimpressed by, Maxim's in Paris. "Art is limited," he began, in a tone that made it clear that he was making no idle observation but reciting the core of his faith as a cook, "but the taste of nature is unlimited. No matter how a dish is prepared, if it is served and eaten often enough, it will no longer convey nature's taste. The preparation of food changes so as to keep people open to the taste of nature." |

| Over the next several decades nutritionists explored such things as digestibility, amino acids, vitamin and mineral intake, alkaline-acidic balance, allergenicity, salt, fat, cholesterol, metabolic waste products, and hormone and antibiotics. Each time a new issue arose, someone would check how the soybean rated, and time and again the bean would be shown to do very well compared with other foods. However, as impressive as these discoveries might have been to nutritionists, they triggered no great consumer demand in the West. |

The land we drove through was as flat as an airport apron. It seemed only about three inches higher than the Mississippi River; flooding, Box said, was a constant threat. About half of the bare handful of houses we passed were raised on thick stilts, and from a distance they seemed to be walking across the fields. "Last big flood we had," Box said, driving into the Fullens' place, "I came down here in my boat, tied up to the porch, and stepped right out." The porch was a good five feet off the ground. |

Jim Fullen and his sons, Steve and Jimmy, farmed about 5,000 acres of soybeans in partnership with Box. Our meeting had a somber mood. The price of soybeans in relation to the cost of production was way down, and soybean farmers were under serious financial pressure. Many - one estimate I heard was one third - were not expected to make it, though Fullens themselves thought that they would. |  |

However, the course of postwar politics and the difficulties experienced by the Chinese in recovering from wartime devastation prevented the restoration of prewar trade relations with the West. The world soybean market needed a new source of supply, and the American farmer successfully stepped into the position. |

|

Between 1945 and 1985, as the effects of these changes were felt, the US soybean harvest increased in volume 11 times. The bean became the farmer's most important cash crop and the country's leading agricultural export - in 1986 the United Sates exported 3.7 billion dollars' worth of soybeans. |

The bean is less finicky both to grow and handle, which means that more of the agricultural labor can be done by machine. At the time - the 1950s and '60s - this was just one more reason to make the switch, since farm labor was getting scarce anyway. |

These developments depressed soybean prices perilously close to cost - below cost, in the case of many American farmers. Most people I spoke to thought the result would be that the number of people living and working on the land would decline still further. |  |

Meanwhile, the rest of the bean is shipped off to feedlots and poultry producers to feed animals that themselves will eventually end up in supermarkets. Thus over the last 30 years the soybean has become as important to the Western diet as to that of the East. If some virus were to kill off the world crop, the peoples of both hemispheres would find their diet drastically altered. The only difference is that in the West the bean is invisible. Even pure soy oil is usually sold as "vegetable oil." |

| "During the war, meat was in short supply, even in this country, and the government promoted the soybean as a substitute, touting its high protein content and low cost. But after the war, interest in soy foods dropped off, apparently because people continued to identify them with wartime deprivation and the government's emphasis on good nutrition. The American public went back to eating meat." |

Shurtleff, a tall man, whippy as a blackboard pointer, talks glowingly of what he sees as a swing to soyfoods by a new, postwar generation: Tofu and miso are in more and more supermarkets; tempeh sales are up 33 percent. One hundred and fifty new tofu plants have been started in the US since 1975. the most successful soy food ever introduced in the West has been tofu "ice cream", which has grown more than 600 percent in sales over the past two years. (By the summer of 1986 there were 45 brands on the market.) |

"The price of a coconut went up from one rupee to five," Cecil Dharmasena, director of the research center, recalled. "Rajasoya was very successful. Everybody started using it. The factory hired a second shift and began planning a third. Then coconut prices began to slip; they went down to two and a half rupees, and back up to three - still a lot more expensive than they had been, but suddenly people just started paying the higher prices. Sales of Rajasoya plummeted. We went to one shift, two days a week."

There are Sri Lankans, I was told, who prefer soy-milk powder to coconut milk, finding the latter too heavy and greasy, but obviously they are a minority. The research center subsequently develop coconut-soy blends that native Sri Lankans (taste tests seem to show) find more acceptable, but so far no entrepreneurs have been willing to back them in the marketplace. |  |

Another reason why soya might yet succeed in Sri Lanka, at least over the long term, is that the local farmer continue to grow the bean, and in increasing volume. "Who buys your beans? The government?" I asked the farmers. No, I was told, private traders. "And who do they sell them to?" Nobody seemed to know, so, together with Pathiravitana, I visited the Pettah on Old Moor Street in Colombo, headquarters to the traders of Sri Lanka.

|

The information contained in this website is general and not specific to any individual. It is only for reference and education purposes. Do not self-diagnose or attempt self-treatment for serious or long-term problems without first consulting a qualified practitioner, preferably one who is familiar with soya products and alternative medicine. Heilongjiang Soya is the trade mark of Country Food & Beverages. ©2000 Country Food & Beverages. |